As soon as she said “disabled person” I realised what the problem was. Disability is a natural part of life. People with disabilities make up 15% of the world’s population, and include men, women, young, old, our families, ourselves and everything in-between. But when you ask people what they think when you say “disabled person”, you get answers that are pretty specific. Not answers that begin to gesture to a billion people alive in the world right now.

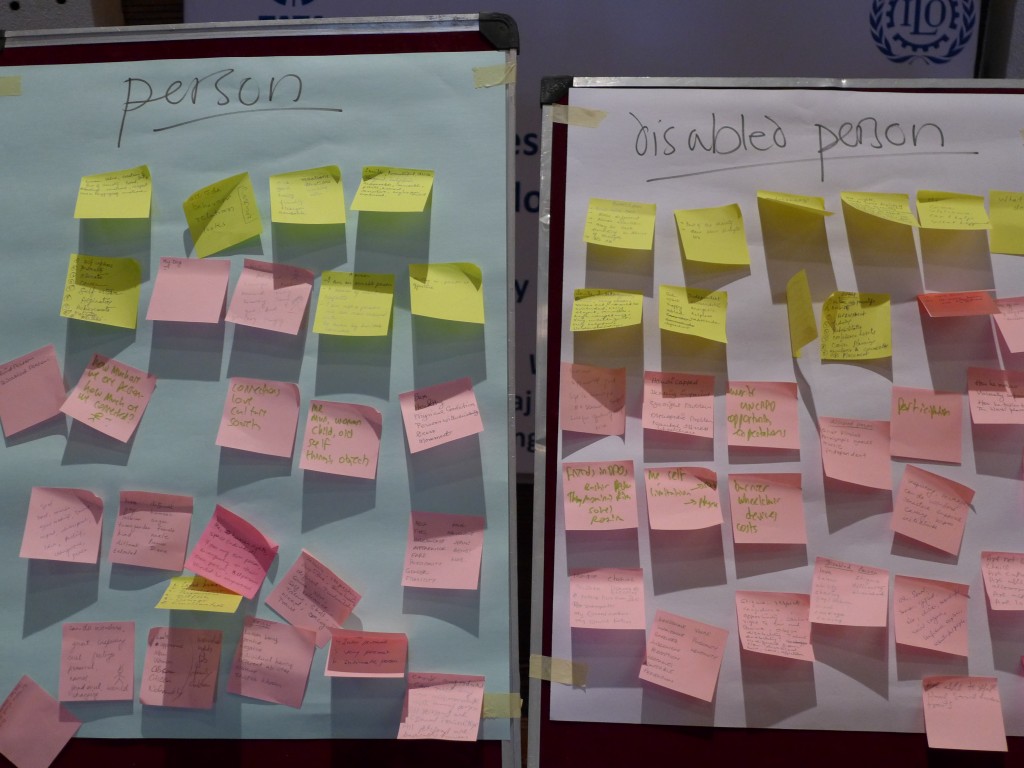

This was part of a Disability Equality Training in Bangalore, and we did an exercise that I’ll definitely be stealing. Our trainer gave us post-it notes and told us to write down whatever came into our head when she said a certain phrase. She gave us one minute each for four phrases. First she said “person” – and then you’re thinking big and writing about your mummy and daddy and good people and bad people and all sorts of things. Then she said “disabled person” – and your view starts to get smaller, you start writing about problems, stigma, specific people, what your work on disability tells you to think, and so on.

Next was “segregate disabled people” – which you might react to with some shock but then there are also some positive reasons for that too, right? Finally, “integrate disabled people”, by which time your mind has done some spins and you know this is a good thing so you write that down but some other issues have awkwardly entered your head so you write them down too. These four minutes turn up enough issues in your group that you have conversation for at least the rest of the day.

I hadn’t realised quite how much “disabled person” occupied a different space in our minds. People with disabilities are segregated in social, economic, emotional and philosophical ways. This exercise showed how these segregations run through our understandings of what “disability” means, and how much they have been formed before we got into the training room. It revealed the different emotional and analytic categories we use and how they’re not always connected. Like me, many of the others were people who’ve worked on disability issues in one way or another. So our buzzwords and right-answers were mixed in with our feelings and personal identification.

Someone pointed out that we took a distance from disability, separating it from our own situations. We had recommendations for what, say, the government should do, but not necessarily ideas about what disability means in our own lives or our jobs. When we wrote on “person” the answers started from ourselves. When we wrote on “disabled person” the answers mostly started on the other, “them” as opposed to “us”.

The journey this exercise took us on was from open reactions to narrow solutions. I think this leaves two challenges for us in the disability sector.

The first is that our work can be part of the problem. We insist on categorising categorising “disabled people” and giving recommendations on what to do with “them”. We do this because we believe it to be useful and necessary, and maybe it is. But it surely also contributes to the other-ing and distancing of this imagined group of people. We need to tread carefully to make sure our administrative and political categories interact positively with emotional ones.

Secondly, the larger message that this exercise gives is on how much work we have to do. We all have such ingrained ideas and feelings about what disabled people are. These ideas and their histories need to be broken open. Our goal is that one day what you write down when someone says “person” and when someone says “disabled person” will be much more similar than it is today.

Thanks to the ILO Global Business and Disability Network and Tata Consultancy Services for hosting the event. And to our excellent trainer, Maureen Gilbert for showing us different ways to think.