It’s hard to describe Bangladesh because some of the first things that come to mind are the things that you don’t like. It’s poor, dirty, unfair, horribly horribly unfair, and inconvenient. I’ll probably tell you about the inconvenience first, the traffic jams, oh, the things that should happen and don’t. “Everything is possible in Bangladesh” is what you’ll be told when something previously impossible has just happened in front of you. Sure. But where everything is possible, the thing you need or expect is not very likely to happen. Things are not where they should be, and things are not as they seem. And there is a wonderful new world to be found in that and in changing your expectations.

আমার সোনার বাংলা আমি তমায় ভালবাসি… সোনার বাংলা আবার কয়? দেখি জ্যামজট, পাই গন্ধ, কাদা, load-sharing, হারতাল। এটা রবীন্দ্রনাথের বাংলা নয়, এটা ঢাকা সিটি. এটা ঈদের chaos এবং ঈদের আনন্দ। ঝগড়া এবং ভালবাসা। যে ভাবে আছ, ষে ভাবে আমি তমায় ভালবাসি আমার নোংরার বাংলা।

In Dhaka, so many of us are trying to get places that we sometimes don’t get very far at all.

Alongside the Bangladesh you see is the Bangladesh you feel. You are pulled and pulled into the urgency and intensity of personal relationships that are so overwhelming here. “What country? How much money do you earn?” these are the opening steps in the dance – but the real character of the dance is found later on in the intimacy of “what are you doing?”, “will you miss me?”, “have you forgotten us?”. I told someone I was leaving and spontaneously, directly and with all sincerity he said that he will remember me for the rest of his life.

You can get used to the unfair and the inconvenient. Bangladeshis and foreigners alike, we are all struggling with it in Bangladesh. We are all getting used to it one way or another, and plenty of us, Bangladeshis and foreigners alike, are leaving or looking to leave. In the face of uncertainty, injustice, a political space with no room for people to express themselves, and extreme social and economic constraints, there is infinite room for one more thing – feelings. In a space where you have no room for movement, but everything is changeable, love, hate, kindness, and tyranny all flourish. ভালবাসাটা বেশি, মনে করি আমি।

It’s the love that’s still overwhelming. I’m not even sure of the name of the person who said he will remember me for the rest of his life. There are so many, so many relationships and people here that people have given love so intensely. I have only been able to return it in a small way. I have been lucky to be brought into a family, “adopted”, and with that to have gained a Baba (remember him in your prayers), a Ma, two brothers and a sister, their families, and cousins and aunts and uncles and in-laws. It fills me with joy when I am sitting next to Ma, someone asks who I am, and she replies “my son” without any explanation, except sometimes to add that I am the “younger” son. Understand what you will.

মা, আমি বাংলা বলি যেন তুমি বুঝতে পার। যখন তোমার পাশে বসি আর কেউ প্রশ্ন করে, “সে কে?”, তখন তুমি বল “আমার ছেলে”, আর আমি খুব গর্ব বধ করি। আমাদের ভালবাসা এবং পরিচয়ের বর্ণনা করার জন্য আমি শব্দ পাচ্ছি না। যে ভাবে আমি বাসা আসতাম, যে ভাবে আমি তোমাদের সাথে ঈদ পালন করতাম… একসাথে আমরা অনেক আনন্দ করছি, আর একসাথে আমরা কিছু দুখও পেলাম। আস্তে আস্তে আমাদের পরিচয় আপন হয়ে গেছে। মা, আমি জানি যে প্রতিদিন তুমি আমার কথা মনে রাখ। মা, আমি আশা করি তুমিও জানো যে আমার মনের মধ্যে তোমাকে নিয়ে যাব।

My Bangladeshi Ma, Boro Bhai, Boro Apu and Shaitan.

I haven’t found, yet, the way that I would like to live in Bangladesh. I wanted at first to become Bangladeshi, to absorb as much as I could. I learned how to say আমি বাংলা হতে চাই, I want to be Bengali, the same day I bought my first lungi. I searched and searched for the authentic and then I stopped searching. Some of the reason I stopped searching is my work that puts me in an English-speaking, air-conditioned office; some of it is my comfort that makes it easier to have an apartment and a driver and etc; some of it is my disability, that limits the way I roam the fields and the lanes, that keeps me in the places with the western toilet, that limits me in roaming the streets of Dhaka. Some of it is simply that I am who I am and there’s a limit to how much one person can explore, and I don’t have the drive for it that I did before. Some of it is that I have found the authentic, and nurture relationships across Bangladesh with all sorts of people. It’s not quite the life I would like, yet – a social life that’s full at the same time as being so lacking, a life that’s constrained at the same time as comfortable, a life full of discoveries as one cuts oneself off from different parts of the world. Or discoveries about different parts of the world as one cuts oneself off from Bangladesh.

I got my first job in Bangladesh. Not long after starting my Baba said to me that ah, you are just one of the foreigners taking the poor people’s money, Britishers give money to Bangladesh and then British people come and take it in salaries and cars before it gets to the Bangladeshis. And leaving this time, I met with some “beneficiaries” of a project I was part of, and they had a similar line – সবাই খাইসে, শুধু আমরা খাই নি, everyone got money, except them, the people who it was supposedly for. In my first year here I was at a “social protection” conference in a fancy hotel. We were discussing the benefits the government gives, which are in the range of a few dollars a month. The lunch buffet was worth 5-10 of these monthly allowances.

খাইসে, খাইসে। সবাই খাইসে। আমিও খাইসি।

And now my career is closer and closer to that conference. When you get flown about between places you don’t know what’s going on the country, you lose the sense of the absurd luxury that you are in compared to local standards. You just compare it to your allowance, and your allowance is too high. The main information you get about the country is from your colleagues, the ones that speak English. It’s a one-dimensional view. I am on my way to Geneva, where people will say I was in the “field office”. I was not in the field. I was in the posh part of the capital city, tapping away at my laptop, complaining about traffic jams and comparing the new restaurants that opened.

A lot of my work in Bangladesh looked like this.

বাইরে গিয়ে, আমি কার সাথে বাংলা বলব? এখুন আমার কথা বুঝবে কে? আমি বাংলা ভাষা শিখে অনেক মজা পেয়েছি। এমনি ভাষাটা সুন্দর, এমনি বাংলা নিয়ে thinking করা একটা মজা আছে। কিন্তু আমার সবচে বড় পাওয়া ছিল যে বাংলা শিখে আমি এত নতুন দৃষ্টিবঙ্গি পেয়েছি। সবাইয়ের সাথে কথা বলতে পারলে আমি শুনতে পেরেছি বিভিন্ন ইতিহাস আর জীবনের গল্প যে আমার নিজের ইতিহাস আর জীবন থেকে একেবারে আলাদাহ হয়। বাংলা শিখে অনেক জানেলা খুলা হয়েছে আমার মনের মধ্যে। এই জন্য আমি বাংলাদেশ থাকতে এত পছন্দ করি, এই জন্য আমি বার বার আসি, বার বার আসব।

I am happy with the Bengali I have learned and the understanding it has given me of the country and culture. I don’t know how colleagues can come here and not learn it. How can they understand what’s going on? Why don’t they get frustrated by all that’s getting lost in translation? I realised, slowly, we all have different talents and different ways of communicating and it is not for everyone to come in the way that I have. But I also realise that being able not just to speak Bangla but to understand other people’s points of views has deeply enriched the way that I work. Both the way that I interact with colleagues and in the way I can make suggestions. People often say the thing they like most about working with me is that I speak Bangla – I like to think it’s not just the language, but the way I engage and try to share and try to understand what their situation is, not just what their situation should be.

Here in Bangladesh I can work more honestly than I can work in other countries. I can check in with colleagues a couple of years after we’ve tried something to see how it turned out. I can go back and visit people. I can do projects in my spare time. I can be part of a movement of friends and colleagues that are struggling to do things, inside or outside of their professional work, whether we are paid for it or not.

From living and working here I have learned how fake and how useless “development aid” can be. I have been extremely frustrated not with the outside systems – Bangladesh is corrupt, yes, sure, that’s why we’re here – but rather with the systems within the offices where we work, where we don’t practice what we preach, where we let problems continue, where we reproduce the hierarchies and inequalities we are meant to be challenging.

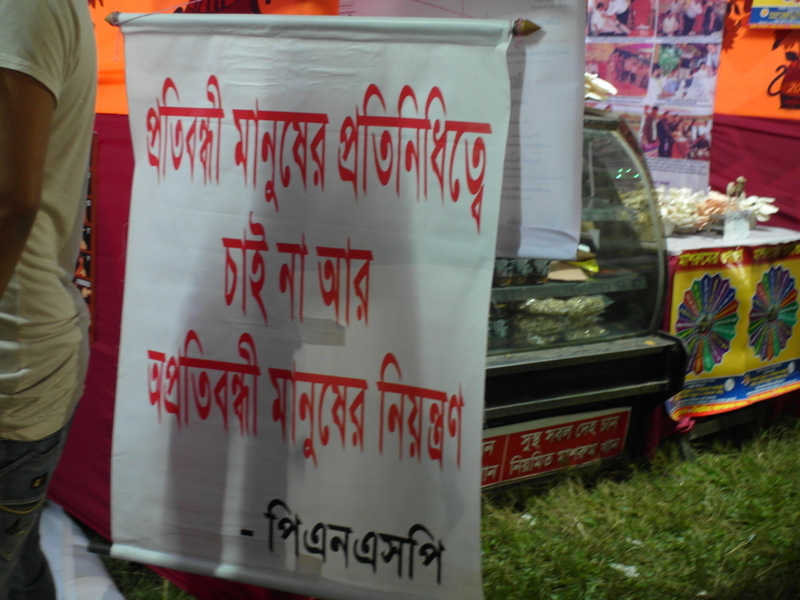

At the same time, from my work and from my friends, I have learned what real social change looks like. I have friends with disabilities who have lived through change in their lifetimes, from being isolated to being important members in their communities. I have seen the many ways you can wheedle and encourage and try and try again to get people in power to make changes and to achieve a fairer world. I know from this more about the person that I want to be and the role I want to have in the world. My time in Bangladesh has shown me what purpose might look like, and what you have to do to achieve it.

প্রতিবন্ধী ভাই বনরা, আমি তোমাদের কাছ থেকে অনেক কিছু শিখলাম। তোমরা অনেকে জান কি বাংলাদেশের আসার আগে আমি এই ভাবে প্রতিবন্ধীটা বিষয় নিয়ে কাজ করি নি। আমি তোমাদের কাছ থেকে শিখলাম আন্দোলন করা মানে কি। আমি তোমাদের কাছ থেকে শিখলাম লেগে থাকা মানে কি। তোমাদের কাছ থেকে আমি শিখলাম লড়াই করা মানে কি।

Sitting with friends with whom I have discovered myself and the world.

যখন অন্য দেশের অবস্থা দেখি, তারা সব কিছু টাকা দিয়ে সমাধান করতে চায়। বাংলদেশে আমাদের টাকা নাই, আর এই জন্য আমরা অন্য উপায় পাচ্ছি কাজ করার জন্য আর আমাদের অধিকার পাওয়ার জন্য।

I don’t yet know how to balance the two. My career has been a story of learning to accept things I was previously frustrated with. I realised, during a contract negotiation, that I had “sold myself”, that I was just doing it for money. So I left. I was back a few months later. Since coming back I’ve learned to sell myself for more money. I’ve also learned what the possibilities are to do things closer to what I believe in, both inside and outside of my professional work. And (fortunately? unfortunately?) I’ve learned how to accept and reproduce the parts I don’t believe in. I’m not sure which way lies in the future.

Leaving Bangladesh now I am happy that I was able to influence people and make some things happen in the same way people have influenced me. I am proudest of the personal relationships I built with colleagues and friends, where, at their best, what we have shared has changed the way both of us have done things. To some extent I have been a positive example.

To some extent I have failed in my work. Well let’s not put it like that, because on my CV I’m putting them as successes. There are things I worked on that I am disappointed by. We didn’t support people as much as we should have or as much as we promised we would, or as much as the people needed. I’ve done a lot of talking and written a lot of documents and been in a lot of meetings, and it’s not always easy to see how, outside of the artificial world of projects and deadlines and indicators, it has led to anything useful. …

In theory, it’s been fascinating living in Dhaka and Bangladesh at this time. We will be able to say afterwards that we lived through a process of rapid social change and didn’t notice a damn thing. In Bangladesh you can never be sure whether your plan for tomorrow will come through, so you lose sight of the bigger picture. Bangladesh is a young country, born in so much pain in 1971. The original “bread basket”, Bangladesh has since then doubled in population. But even though its GDP per-capita is less than India or Pakistan, in many social indicators it’s doing better than its neighbours. Bangladeshis have better life expectancy than Indians or Pakistanis. Lower infant mortality. Fewer child deaths. Fewer maternal deaths. Higher immunisation of children. Higher female literacy. Even though Bangladesh is a desperately unfair society, in many ways we are doing better, with fewer resources, than our neighbours. People from India and Pakistan are often quite rude about Bangladesh, but unfortunately for them, these statistics speak louder than their words ever can.

I should also add that Bangladesh, outside of Dhaka, is beautiful.

আমি এই বাংলা সাহস করে লিখছি। আসলে আমার বাংলা লেখার অভ্যাস নাই। মনে হয়েছে কি একজন শিক্ষকের কাছ এই লেখার চেক করে নিব। তারপরে মনে হল কি, ভুল থাকলে ভুল থাকুক। ভুল তো আমারই। আমি যদি ভাল করে শিখতে পারি নি, দোষ তোমাদের। আমাকে শিখাও নি কেন?

I am leaving Bangladesh feeling that there’s so much I’ve learned, but also that there’s so much left to learn. My Bangla is fluent but there are so many ways it could be better, and there are still plenty of conversations I can’t follow, even of people close to me. There are so many things about life and culture and the country that are entirely unknown to me. Each of us takes our own way to explore a country, whether it is our own or not. In making Bangladesh my own it is also clear how many parts of it I don’t know and maybe never will. In making Bangladesh my own, my understanding of the world and how to relate to people has changed.

প্রিয় বন্ধুরা, তোমাদের সাথে আমি বড় হয়েছি। কোন ভুল থাকলে আমাকে ক্ষমা করে দাও। আমি ফিরে আসব।

I will come back. There are people here that will be part of my life forever, and we will explore the future together. There is plenty of work here to be done, some that I can get paid for, some that I believe in, some that’s both. On leaving, the most interesting questions are ahead. What has my time in Bangladesh turned me into, and what will I do with that? My connections with this place, its people, the Bangladeshi diaspora and Bangladesh-lovers across the world – what will these turn into? The restless uncertainty and striving of life in Bangladesh, কালকে কি হবে, is one that I take forward. যা হবে, তাই হবে। আমরা একসাথে আছি।