I was speaking English…

I was giving a session on disability in Indonesia. A translator was turning this into Bahasa. There’s plenty of space for confusion in that alone. But a further translation was also being doine, by another interpreter, who lip-read the Bahasa and put it into sign-language.

The training was for 40 disabled people who’d just completed a skills training program. These 40 people had come from all over Indonesia and had been together for a month or two. We were preparing them before they started work and I was telling them about the social model of disability. Some of them had a high level of education and could speak with me in English, others hadn’t. Something over 10 people were using sign-language to communicate, and they too had different levels of proficiency using sign.

Ok, I told you all that as an excuse: not everyone could follow what the session was about. Plenty of people did, though, and it was pleasing to see how quickly they could identify the difficulties they had at an individual level (having a leg problem, not being able to hear) and those they had at a “social” level (difficulties using public transport, not being able to find work). Many of the participants were able to describe this well by the end, and the hope is that this idea will help them see their lives differently. But there were several people who didn’t follow.

Talking about access needs, but not solving access needs for people there.

It was clear by the end that not everyone had followed what was going on, and that difficulties in the translation from English to Bahasa and then Bahasa to sign-language had been part of the difficulty. This was upsetting. We were busy talking about social exclusion but hadn’t found a way to effectively include everyone in that discussion. It was hard to admit at the time, but my own role was part of the problem I am supposedly trying to address. And it’s hard to admit that even though I’m an “expert” some of this was new to me.

There are various ways that we didn’t provide good accessibility for the trainees. One of the training centres they were in was on the 2nd and 3rd floors, and our sign-language interpreter wasn’t available to all the trainees all the time. Nonetheless, both physically disabled people got up the stairs and the deaf trainees were able to learn also. The people giving the training course said that communication was hard at first by they learnt to do it in different ways. So in fact this shows that even when you don’t have full – or even partial – accessibility in place you can still do something effective and useful.

A thin line between inclusion and exclusion.

My session was one of the cases that showed the limits of the inclusion. “Inclusion” of different trainees was partial, and always at risk of crossing over into exclusion. It was clear from the way my colleagues and myself were communicating that people were often being left out. In the closing ceremony we did to celebrate having done the training for disabled people, I think there were parts that the people we were celebrating couldn’t follow, again because we didn’t pay enough care into putting things into sign-language.

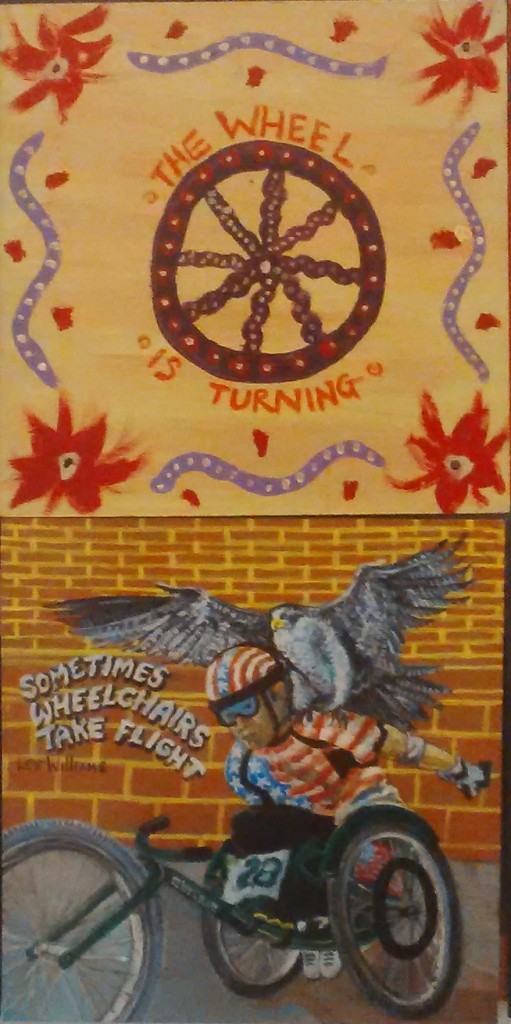

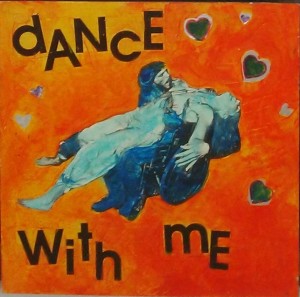

I know from my own life that inclusion is a continuous process, something relevant at each set of steps or when I stand up from a chair or when we are going somewhere. I know the kindness and love of people looking out for this, and I know how painful can be when people forget or ignore it. Exclusion can be sudden, personal and we can react to it with anything from laughter to patience, fear or anger.

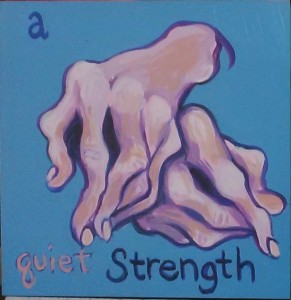

We can’t expect true accessibility and inclusion to come about as mere add-ons.

Just because we’ve gotten a sign-language interpreter doesn’t mean that deaf people will be able to follow everything. We needed to slow some things down and deliver some things slightly differently to make sure everyone could follow and participate. The colleague I was working with pointed out to me the extent of the problems in communication and suggested that an alternative would have been to do individual or smaller-group sessions for some of the participants. Good idea: not everyone is going to be able to follow a group session at the same speed. We know this clearly from learning in schools, but often we don’t think about this when we’re designing a training and identifying the time or resources we need for it.

I wrote this post in the first person because it was an important realisation for me. I realised how many of the communication styles I take for granted don’t work for everyone. I know from these trainees that I can’t just walk into a room, start talking, and expect that everyone will follow. Even when people are following, then there are those getting left out. These group discussions are such a staple of development work – we’re always doing some sort of training, committee, or focus group discussion. In Bangladesh I’ve learned to speak Bengali as one of the ways to make sure I communicate better with people. That’s not enough. My experience from both this and other meetings is that I (and many of my colleagues) have a way to go if we want to facilitate these sessions in a fully inclusive way.